Download this article as a PROTECT Project Policy Brief in pdf-format here

Summary

- With an annual value of €2 trillion, public procurement is a key driver for green and digital transformation, involving 250.000 European contracting authorities

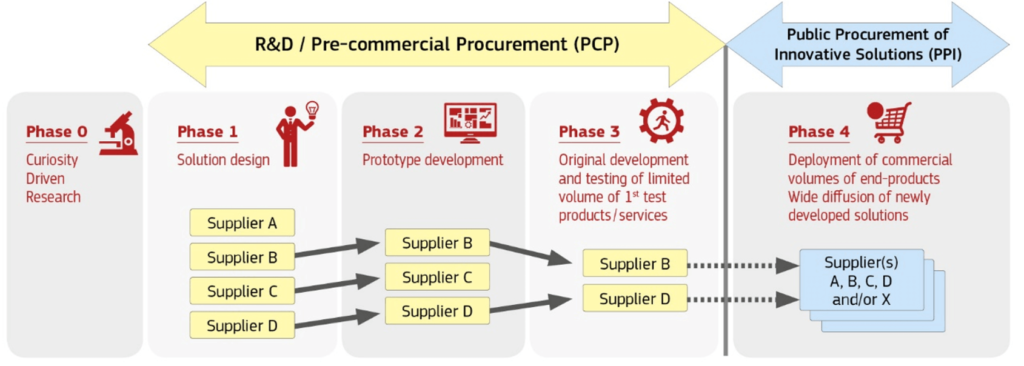

- If there are no solutions available in the market to satisfy a current or future genuine need, public authorities can resource to the Pre-Commercial Procurement (PCP) approach to purchase R&D services from different technology providers who compete throughout phases of solution design, prototype development and testing and validation.

- PCP falls outside the WTO-GPA and the EU Public Procurement Directives. The flexibility of the PCP approach enhances competition and mitigates risks. In the PCP approach, procurers share the IPR related risks and benefits of undertaking new developments with the R&D providers participating in PCP. This approach maximizes the incentives to commercialise the developed solutions to other markets.

Introduction

Traditional procurement is based on short-term tactical purchasing considerations, usually prioritizing low cost over quality, or looking only at immediate instead of longer-term cost/quality impact [6]. Lack of knowledge about technological solutions often leads to over or underspecified tender specifications. When procurement decisions are driven more by considerations to avoid deployment risks (fear to introduce ‘new’ solutions) instead of maximizing cost/quality improvements, this often leads to suboptimal overall value for money and technology/vendor lock-in. It is understandable that the obligation to wisely spend taxpayers’ money makes procurers inevitably risk-averse.

However, when innovation procurement is implemented as a smart PCP/PPI combination, it becomes a strategic tool to systematically improve the quality/efficiency of public services whilst minimizing the risks of deploying ‘new’ solutions. PCP enables procurers to de-risk novel technologies, remove supplier lock-in, and gain invaluable insights into the pros and cons of competing solutions ‘before’ making any commitments to deploy large volumes of solutions.

Policy developments

PCP was defined in 2007 in the PCP Communication in full compliance with the legal framework Parts of the PCP Communication have been included in later legislation: The 2014 public procurement directives clarify that PCP is exempted from its remit and the 2014 State aid framework for Research and Development and Innovation clarifies the conditions under which PCP is done according to market conditions.

PCP, due to its characteristics is exempted from the GPA of the WTO and consequently of the EU Public Procurement Directives. This is of particular interest to foster European strategic autonomy and resilience, since contracting authorities may require the performance of the R&D services to take place in Europe, which in turn strengthens Europe´s technological potential and increases the resilience of Members States to potential supply chain disruption in emerging technologies. It also supports the goal of having an autonomous Europe when it comes to key enabling technologies.

The use of multiple sourcing in pre-commercial procurement also strengthens EU strategic autonomy and resilience. By triggering in a forward looking way a range of suppliers to develop new innovative solutions that can address upcoming mid-to-long term procurement needs, public procurers can bring in competition from new innovative companies into a supply chain that was previously plagued by supplier lock-in, or build up a totally competitive pool of European suppliers that can address its strategic needs in the future with solutions that are ‘made in Europe’.

The IPR and commercialisation conditions that can be used in pre-commercial procurement also contribute to fostering EU strategic autonomy. It is a key characteristic of PCP to leave the IPR ownership rights with the participating contractors so that they can commercialise their solutions more widely, which increase the range of European suppliers able to deliver solutions to the public sector, thus enhancing resilience and strategic autonomy.

This comes with a condition to commercialise the solutions within a specified time. This condition can be extended with the requirement to perform the majority of the commercialisation activities in Europe (e.g. production, marketing, service delivery facilities) also after the PCP contracts ends.

In addition, the procurer can restrict exclusive transfer and licensing of the results/IPR from the PCP to non-EU suppliers. An IPR call back clause ensures that the public procurer can require IPR ownership rights to be transferred back to the procurer in case a supplier does not respect the PCP’s place performance conditions, establishment and control from Europe obligations, IPR obligations or commercialisation obligations or in case other EU strategic autonomy or essential security interests are compromised (e.g. in case of a merger or acquisition of a PCP supplier by a non-EU entity).

Conclusions

Public organizations can perform more R&D procurement on strategic key technologies through the PCP approach, to avoid becoming overly dependent on non-EU suppliers by requiring R&D to be done in Europe. This gives vendors a first mover advantage and ensures that there will be vendors in Europe who can deliver solutions.

By using a phase approach and multiple sourcing, the number of suppliers that can deliver solutions increases, reducing supplier lock-in, and thus increasing resilience in case of supply chain shocks.

Leaving IPR ownership with suppliers in procurement – as in the standard approach in Europe – enables more vendors to commercialise/offer solutions to procurers, on the condition that vendors will keep a significant part of product commercialisation in Europe (e.g., minimum 50% of the production). In this regard, a measure could be set to allow vendors to do ‘exclusive’ licensing or transfer of IPR/results to non-EU players only after approval of the procurer. It is important to keep the right to call back IPR in case of mergers/acquisition of contractors by non-EU players.

Another measure is to keep the right to call back the ownership of IPR/results, in case of noncompliance with any of the place of performance, control from Europe, commercialisation, IPR, security etc. obligations (e.g., EU blockchain PCP). Announcing the mid-to-long term procurement needs more in advance to the market is fundamental to alert all actors in the supply chain to get ready to provide solutions (e.g., climate neutral solutions).

Recommendations

- A key instrument to steer and speed up R&D is the competitive approach in phases and shared risk/benefit of Pre-Commercial Procurement (PCP).

- The PCP approach has proven benefits like speeding up the time to market of innovative solutions, while creating opportunities for European companies (in particular SMEs) that can grow in new market segments based on the public demand.

- A PCP can stimulate the participation of international companies, bringing together several public organisations for a joint crossborder procurement, making use of the Horizon Europe Programme.

- A proper step-by-step preparation of a PCP based on functional requirements increases the success of a project

Download this article as a PROTECT Project Policy Brief in pdf-format here